Searching for the Six Mile Stone

Setting out on journeys through life: Hazlitt, Coleridge and the Shrewsbury Road.

Why can we not revive past times as we can revisit old places? If I had the quaint muse of Sir Philip Sidney to assist me, I would write a Sonnet to the Road between Wem and Shrewsbury, and immortalise every step of it by some fond enigmatical conceit. I would swear that the very milestones had ears, and that Harmer Hill stooped with all its pines, to listen to a poet, as he passed!

(William Hazlitt, My First Acquaintance With Poets, 1823)1

i

In a previous post, History as a Way of Love, I write about poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge visiting and staying with the Hazlitt Family in their house at 17 Noble Street, Wem. As a child, the white exterior of Hazlitt House was visible from my bedroom, across the road, at Trentham House. There was a rectangular stone-carved plaque set into the wall, above the front door, that indicated something special about it. Local kids walked past it, but not much was said about it. My mother and a line of five other laughing housewives ran past it, flipping pancakes for the annual Noble Street pancake race, one year. But maybe it was the unusual name that stuck.

Revisiting the town over the last couple of years, Hazlitt House is much bigger than I remember. The 18th Century brick house has two storeys and four bays of lead panelled casement windows. It was built by George Tyler after his appointment as curate of Wem in 1727. After Tyler's death in 1747, the house was purchased for the manse of the Presbyterian chapel adjoining it, and was home of the Revd William Hazlitt from 1787 to 1813; his son William, the essayist and critic lived there until 1799.

William Hazlitt was born in Maidstone, Kent, on April 10 1778. Hazlitt's mother, Grace Loftus, was the daughter of a Suffolk Unitarian ironmonger; his father, also William, was from a family of northern Irish Presbyterians, who had moved to the south of Ireland, where he was born in the town of Shronell, co. Tipperary, in 1737. Rev. Hazlitt was influenced by the Ulster-Scots philosopher Francis Hutcheson through his studies at Glasgow University, and through Unitarianism, which he chose in rejection of the Calvinist Presbyterianism of his parents. He was friends with Joseph Priestley, outspoken proponent of Unitarian principles, scientist, and inventor of carbonated water. The Unitarianism or Rational Dissent, promoted by Priestley became central to William Hazlitt junior's writings, even though he was not particularly a religious advocate.

For the young William Hazlitt, Coleridge's North Shropshire visitation was a life shifting moment that ultimately propelled him away from his father's vocation as a non-conformist minister, towards a full life as an essayist and critic of long lasting historical repute and high regard.

ii

Coleridge arrived late in Shrewsbury on Saturday 13th January 1798 and preached his first sermon at the Unitarian Church the next day. Lacking a source of income, he had provisionally taken up an offer to replace Rev. John Rowe (who, ironically, was taking a post nearer to Coleridge's patch, at Lewins Mead Chapel, down in Bristol). Nineteen-year-old Hazlitt walked ten miles from Wem to Shrewsbury and arrived, cold, wet and muddy to hear the anticipated sermon. Coleridge ascended the central pulpit and launched in:

And he went up into the mountain to pray, HIMSELF, ALONE!

Hazlitt was transfixed. ...those two last words which he pronounced loud, deep, and distinct, it seemed to me who was then young, as if the sounds had echoed from the bottom of the human heart, and as if that prayer might have floated in solemn silence through the universe2.

Hazlitt had the long walk back, but he was high as the winter sun in the sky which, despite being softened by a heavy mist, he couldn't help but see as 'an emblem of the good cause.'

The following Tuesday, Coleridge, having been invited to be a guest of the Hazlitts, walked the same ten miles along the Shrewsbury Road to Wem. He found the Noble Street house, was welcomed in and launched into an animated conversation with the family. Whilst eating Welsh mutton and turnips, they discussed the French Revolution, William Wordsworth and Mary Wollstonecraft, whom Coleridge rated as a woman possessed of rare powers of conversation. The discussions went on late into the night. William was further enthralled.

Coleridge stayed the night and the next morning announced that he had received a letter from his patron, Thomas Wedgewood, offering him a £150 annuity to give up the position at Shrewsbury and become a full time writer of poetry and philosophy. The Hazlitt's hearts sank as Coleridge bent down to tie his shoelace and shared his unwavering decision to accept the offer. Seeing the young Hazlitt's disappointment, Coleridge requested a pen and paper on which he wrote - Stowey eight miles from Bridgewater. He handed it to Hazlitt - I would be glad to see you in a few weeks time, he said as he moved towards the door. Hazlitt was delighted and asked if he could accompany Coleridge on the road back to Shrewsbury. Of course, was the reply.

Hazlitt and Coleridge walked out of Wem and onto what is now the B5476. At the Tilley crossroads there was a track up to Trench Farm. Hazlitt may have known that John Ireland, the first significant biographer of the painter William Hogarth, was born there in 1749. In fact, Ireland's biography was published in March 1798, just after Hazlitt and Coleridge met. Hazlitt would go on to write about Hogarth and reviewed the first major Hogarth exhibition at the British Institute, for The Morning Post in May, 1814.

The animated conversationalists carried on up, what is known locally as the mile straight, and past the first mile stone at the Upper Trench track. Though, the conversation was weighted towards Coleridge, as Hazlitt reports: He talked the whole way...In digressing, in dilating, in passing, from subject to subject, he appeared to me to float in air, to slide on ice. They progressed past The Drumble, a small wooded brook, and up the slight incline of Shooters Hill. At the top of the rise, only 300 feet above sea level, they may have glanced over the flat fields of the North Shropshire plains and out to the Welsh Hills in the west. Behind them would have been an open field, as yet unbuilt upon.

iii

Just over one hundred and twenty years later, in that field, forty metres back from the road, a house, to be called 'Shepherd's Top', would be constructed. As a boy and a teenager, in the 1970s and 80s, I would have looked out of my bedroom window, from that house, and seen the same view. Apart from a few more farm buildings at Sleap and the addition of a small RAF airfield (built in 1943 and now the Shropshire Aero Club), not much would have changed.

I was sad when we left Trentham House, on Noble Street, and moved those two miles out south of Wem. Only five bedrooms this time. Built on that slight rise on the Shrewsbury road, in the 1920s, in the Arts & Crafts style, the house had an original character. But it seemed cut off from the town to me. Friends were now a long bicycle ride away. From my bedroom with its sloping ceilings and exposed roof beams, on a limb from the main house and above the garage, I could watch the light aircraft dipping in to Sleap. On some maps the land is marked 'Shepherd's Halt'. In my mind I see farmlands and think of cows when I think of Shropshire. But, the black faced Shropshire Sheep are the oldest pedigree-registered breed in the UK. Could it be Shepherd's Stop? There are reasons for place names. Were there sheep in the field behind poet and acolyte? Hazlitt and Coleridge would not have come across the black face breed, as they were only developed in the 1840s. If there were sheep at Shepherd's Top, they would have been the more hardy, indigenous, slow growing breed with horns and high quality wool. Around the 1800s the system of farm enclosures in Shropshire was increasing and a need for more docile, hornless sheep adaptive to those enclosures was needed. This, including the commercial demand for faster growing sheep, and increased lamb's meat production, stimulated effective cross-breeding programmes over the next few decades.

Shepherd's Top, following Trentham House and, before that, Roden House, was the third and final family home I would live in. From there I came and went to my boarding school at Wrekin College. From there left I school and reintegrated with my Wem friends. From there I grew my hair, became a White Horse pub regular, played darts and pool, fell in love for the first time, developed a taste for intelligent girls from working class backgrounds, formed my rock band Assassin, smoked dope, tried LSD and magic mushrooms. From there I realised trying to be a bird-nut salesman was not my path (a story for another time). From there I briefly worked as a trainee electrician at RAF Shawbury. From there, for a couple of years, I drove in and out of Shrewsbury on my maroon Honda C50 moped, to Besford House, the Children’s home, where I was a Child Care Officer.

At Shepherd's Top, I witnessed my mother die of slow bone cancer, in her bedroom facing the Welsh Hills. There, I felt my mother's spirit leave the top of my head, like a presence withdrawing from its body of pain. She had hovered on the cusp for too long. There I hugged my father, maybe for the first time as an adult, as we reassured ourselves we would be alright. There, I loaded up the yellow Toyota Celica my mother had given me, when she was too ill to drive. There, I paused at the cast iron gates, with their peeling black paint, at the bottom of the gravel driveway. There, the spot where Coleridge and Hazlitt had traversed, maybe paused too. I turned left onto the Shrewsbury road and crossed the twin ghosts of literary history. If I had known it then, I might have slowed down as I came through Preston Gubbals. Here, at the six mile point from Wem, Hazlitt would have said farewell to his inspiring guide, turned round and floated back to Wem. Coleridge would have briskly strolled on to Shrewsbury, to tie up business, prepare his final sermons and pack his minimal belongings for the optimistic journey back down south, into his bright younger years and darker later years.

I drove the yellow car into my long slow maturity and search for independence. At twenty two, I had got on a three year diploma course to study Occupational Therapy at the University Hospital in Cardiff. Knowing I was going to be hanging out with a different crowd, slightly younger than me, and with intentions of 'going straight', I cut my hair, got some new clothes and even bought some non-rock music hoping to fit in. I didn't particularly fit in anyway.

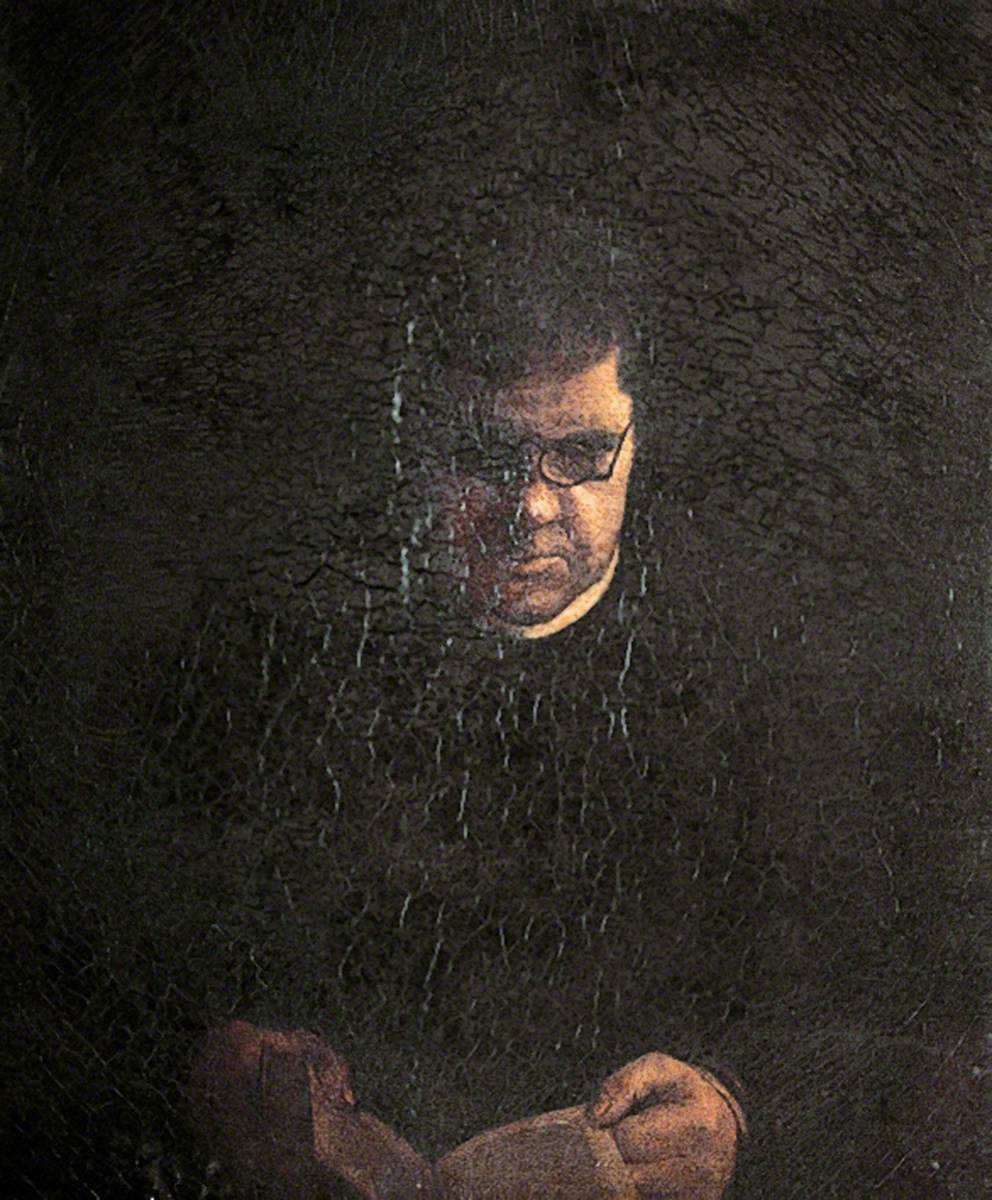

At twenty two William Hazlitt had also moved south, to London, where he was trying to make his way as a portrait painter. In the summer of 1800 he was back in Wem and making trips to Manchester and Liverpool in an attempt to find painting commissions. In 1802 he sat his father down in their house to paint him. He exhibited the painting at the Royal Academy, but the sitting was really an act of father-son connection. They were close in their earlier years but Hazlitt was concerned that his travels and ever expanding lifestyle was creating a schism. Paternal portraiture as healing. Hazlitt fondly recalled his father’s restless moods:

…he grew evidently uneasy when it was a fine day, that is, when the sun shone into the room, so that we could not paint ; and when it became cloudy, began to bustle about, and ask me if I was not getting ready.

They were happy.

In 1831 Hazlitt had a reflective Proustian moment when he heard the letter-bell ringing to announce the postal delivery.

At that loud, tinkling, interrupted sound, the long line of blue hills near the place where I was brought up waves in the horizon; a golden sunset hovers over them, the dwarf-oaks rustle their red leaves in the evening breeze, and the road from Wem to Shrewsbury, by which I first set out on my journey through life, stares me in the face as plain—but from time and change not less visionary and mysterious than the pictures in the Pilgrim's Progress.3

iv

Having passed the future site of my family home at Shepherd's Top, Coleridge and Hazlitt carried on along the Shrewsbury road. They passed the turning to Clive village, where the restoration playwright William Wycherley was born and on towards the four-mile stone at Harmer Hill. Finally they passed through Preston Gubbals and stopped at the six-mile stone. Hazlitt reported:

We parted at the six-mile stone ; and I returned home, pensive but much pleased.

Recently, on my way to see my dad, who still lives near Shrewsbury, I took a short detour through Preston Gubbals. I wanted to see if there was any sign of a six mile marker, old or new, at the place where Hazlitt and Coleridge parted ways. There being no obvious parking place, I just stopped the car on the side of the road by the Preston Gubbals southern boundary sign. It's a busy road, so I switched on the hazard lights. As the cars and lorries slowed down to overtake my road-obstruction, I had an irrational wave of guilt and feigned checking my tyres and the underside of the car. It was like that airport customs anxiety, you know you don't have illegal goods, but you think they are going to get you anyway. Why would a man pull up on a bland piece of Shropshire B road and root around the hedgerow and ditch? Suspicious. I should have brought a fluorescent yellow jacket (I actually have one from an art project I did once, on the River Medlock). Having circled the car several times, displaying a suitably concerned facial expression to reassure the string of cars of my valid situation, I got irritated with myself. Then I got irritated with the passing drivers, whose eye contact I was avoiding. Don't they know this is a psychogeographic hot spot? There should be a bloody blue plaque, or an information board with quotes from Hazlitt and Coleridge, a QR code linking to a fascinating website. Come on Shropshire Heritage! I finally, sheepishly, rooted around the damp ditch, poked in the hedge. Nothing, except ivy, grass, nettles, wild plants and mud. I kicked myself for not giving myself more time to explore further along. On the Google maps street view I had convinced myself that there was a stone marker covered in foliage, waiting to be gloriously discovered, just under the road sign. Not so.

The next day, I got home, bothered with my assumption that the six mile marker was on the west side of the road. The road goes both ways, it could have been on the opposite side. I had to research deeper. Time to delve into the Milestone Society. Maybe this is how any sacred or culturally elevated place is created. Maybe ley-lines are the residual traces of energetic obsessions of meaning-seeking humans.

Many of the 18th century milestones in Shropshire were replaced in the 19th and 20th century by cast iron, white painted, black lettered, triangular marker posts. According to the Milestone Society many of these later posts are now designated as Grade II listed heritage buildings (sic). Several of the remaining cast iron posts on the Wem to Shrewsbury road, including the four-mile post at Harmer Hill and the one-mile post at Upper Trench, are Grade II listed. There is no cast iron post at the Preston Gubbals six mile point. However, I was amazed to find a photograph online of the old stone marker, taken in 2008. The date given by Shropshire Heritage is Late 18th century to Early 19th century (1760 to 1837). The photo shows the stone with the superscription mostly unreadable but the number '4', the miles to Shrewsbury, (implying six miles from Wem) is clearly carved into it. It is possible that this is the milestone that Hazlitt and Coleridge separated at. It is also possible that since 2008 the stone has been stolen. But next time I'm in the area I will have to be more bold, ignore the impatient traffic and get stuck into the ditch. Though I should really park in Noble Street and walk from Wem and back.

Sir Philip Sidney (author of the sonnet cycle, Astrophel and Stella), attended Shrewsbury School.

My First Acquaintance with Poets, first published in the The Liberal, April, 1823 and in William Hazlitt, Selected Writings, edited by Jon Cook (Oxford University Press, 1991)

William Hazlitt, The Letter Bell, 1831